Earthquakes are natural phenomena that can cause significant destruction and loss of life. The primary cause of earthquakes is the movement of tectonic plates within the Earth’s crust.

These plates constantly shift due to the heat from the Earth’s interior, leading to stress build-up at their edges. When this stress exceeds the strength of the rocks, it results in a sudden release of energy in the form of seismic waves, causing the ground to shake.

As tectonic plates grind against each other, the frictional resistance often keeps them locked in place. Over time, the accumulative stress can lead to a sudden slip along a fault line, producing an earthquake with varying magnitudes.

Understanding this process not only highlights the dynamics of our planet but also emphasizes the importance of preparedness in earthquake-prone areas.

Tectonic Forces and Faults

Tectonic forces are key in understanding the generation of earthquakes. They arise from the movement of tectonic plates within the Earth’s crust.

This movement often results in different types of faults, which can produce varying earthquake mechanisms.

Plate Tectonics and Earthquake Genesis

Plate tectonics describes how large sections of the Earth’s crust, known as tectonic plates, move and interact. These plates are in constant motion due to convection currents in the mantle.

As the plates shift, they can become stuck at their edges, leading to a buildup of stress over time.

When this stress exceeds the friction holding the plates together, a sudden release occurs, causing an earthquake. Regions where this happens are often near fault zones, such as the San Andreas Fault, where the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate interact.

This tectonic activity is responsible for many significant tectonic earthquakes.

Types of Faults and Their Mechanisms

There are three main types of faults that are critical in earthquake generation: strike-slip faults, normal faults, and reverse faults.

- Strike-slip faults occur where two plates slide horizontally past each other. The San Andreas Fault is a prominent example.

- Normal faults happen when one block of crust drops relative to another, often in regions of tension.

- Reverse faults occur when one block is pushed up over another, typically found in areas with compressive forces, like those found in the Alpine belt.

In subduction zones, one plate moves under another, creating significant stress and leading to powerful earthquakes. Each type of fault contributes to the complex behavior of Earth’s tectonic system.

Seismic Waves and Earthquake Effects

Seismic waves are critical in understanding how earthquakes impact the earth. These waves travel through the ground, causing damage and varying effects in different regions. Their characteristics dictate the intensity and extent of destruction experienced during an earthquake.

Characteristics of Seismic Waves

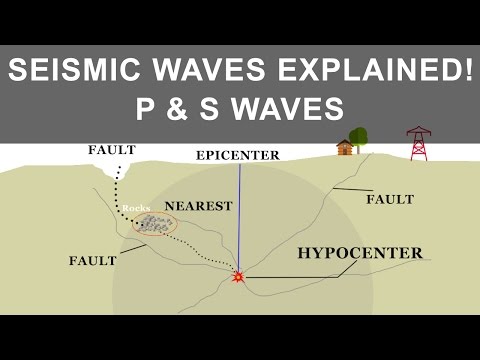

Seismic waves are primarily divided into two types: primary (P) waves and secondary (S) waves.

P waves are compression waves that travel fastest and arrive first during an earthquake. They can move through solids and liquids. In contrast, S waves are shear waves that only move through solids and arrive after P waves.

Additionally, there are surface waves, including Love waves and Rayleigh waves.

Love waves move side-to-side, causing horizontal shaking, while Rayleigh waves create an effect similar to ocean waves, causing both vertical and horizontal ground movement.

The magnitude of these waves can vary, affecting areas like California, Japan, and New Zealand differently based on their geological structures.

Calculating Magnitude and Intensity

Earthquake magnitude is measured on the Richter scale or moment magnitude scale (Mw).

Each increase of one on the scale represents a tenfold increase in amplitude of the seismic waves and approximately 31.6 times more energy release. For example, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake releases significantly more energy than a magnitude 6.0 earthquake.

Intensity, on the other hand, measures the effects of an earthquake at specific locations and is often assessed using the Modified Mercalli Intensity (MMI) scale.

Areas like Chile and Alaska experience varying intensities due to their proximity to fault lines and the Pacific Ring of Fire. Data from seismic readings help in emergency planning and preparedness for future events.

Consequences of Earthquakes

The consequences of earthquakes include physical damage and significant risks like tsunamis.

When a significant earthquake occurs underwater, it can trigger a tsunami, impacting regions far away from the quake’s epicenter.

For instance, in New Zealand, earthquakes can lead to aftershocks, which add to overall damage.

Damage can vary widely based on location, building structures, and preparedness levels.

Earthquakes can cause destruction to infrastructure and endanger lives.

Emergency planning is vital, especially in earthquake-prone areas, to mitigate these risks and ensure safety.

Understanding seismic waves is essential for improving response measures and construction practices in regions vulnerable to earthquakes.