Faults in the Earth’s crust are fascinating features that reveal much about the planet’s dynamic nature.

A fault occurs primarily due to the movement of tectonic plates. This movement generates stress that can exceed the strength of the rocks, leading to fractures in the crust.

When these faults slip, they can cause significant earthquakes, altering the landscape and affecting human structures.

Understanding the causes of faults is crucial for assessing seismic hazards.

As tectonic plates interact, they can push against each other or slide apart, creating areas of intense pressure.

This accumulated stress builds up over time until it is released suddenly, resulting in an earthquake.

The relationship between faults, earthquakes, and tectonic activity highlights the importance of studying these geological structures.

As researchers study faults more closely, they gain valuable insights into the Earth’s history and potential future activity. This knowledge is vital for communities living near fault lines, allowing them to prepare for the unexpected.

By examining the causes and effects of faults, one can appreciate the complex processes that shape our planet.

Fault Mechanics and Movement

Fault mechanics refers to the processes that lead to fault formation and movement within the Earth’s crust. Key factors include stress and strain, interactions between tectonic plates, and the role of friction.

Stress and Strain in the Earth’s Crust

Stress in the Earth’s crust occurs when tectonic forces apply pressure. This stress can result in different types of strain, such as compression, tension, or shear.

Compression occurs at convergent plate boundaries, where plates push against each other, potentially causing reverse faults.

Tensional forces appear at divergent plate boundaries, leading to normal faults as plates pull apart.

As stress continues to build, it may exceed the strength of the rocks, causing a fault to slip. This displacement can result in earthquakes.

The stored energy from stress is released suddenly, causing the ground to shake.

Over time, constant stress may lead to gradual movement in a phenomenon called creep, where rocks shift slowly without significant earthquakes.

Tectonic Plates Interaction

Tectonic plates are massive sections of the Earth’s lithosphere that move and interact at their boundaries. These movements create a variety of faults, including strike-slip faults, where rocks slide past each other horizontally.

At convergent boundaries, the plates collide, resulting in compression and the formation of reverse faults.

In contrast, at divergent boundaries, plates move apart, causing extension and normal faults.

The constant interaction between these tectonic forces shapes the landscape and triggers seismic activity, including earthquakes. Understanding these interactions can help predict fault movements and the associated risks.

The Role of Friction

Friction plays a critical role in fault mechanics. It is the resistance that rocks encounter when sliding against one another.

When stress builds up, it may initially overcome friction, leading to sudden fault movement. This sudden slip causes energy release, resulting in earthquakes.

In some cases, rocks can remain locked due to high friction, delaying movement until the stress becomes too great.

This buildup and eventual release of strain energy are crucial in understanding how surface movement occurs. Therefore, friction is essential in determining when and how faults slip, influencing the timing and intensity of seismic events.

Types of Faults and Their Characteristics

Faults in the Earth’s crust can be classified based on their movement and structure. Understanding these classifications helps in grasping how they impact geological formations and seismic activity.

Classification of Faults

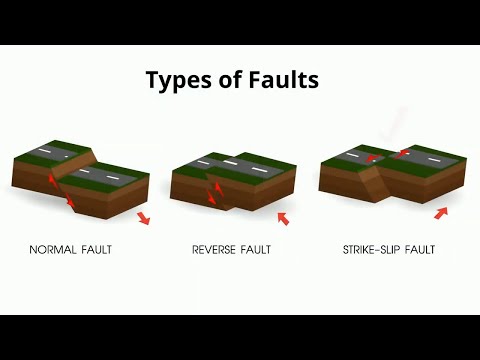

Faults can be broadly classified into different types based on their movement. The primary classifications are:

-

Normal Faults: Occur when the hanging wall moves down relative to the footwall. They form in extensional environments, such as rift valleys.

-

Reverse Faults: The hanging wall moves up relative to the footwall. These typically occur in regions experiencing compression.

-

Thrust Faults: A type of reverse fault with a low-angle fault plane. These faults are common at convergent plate boundaries.

-

Strike-Slip Faults: Characterized by horizontal motion where two blocks slide past each other. The San Andreas Fault is a prominent example.

-

Oblique-Slip Faults: Combine vertical and horizontal movements, resulting in both dip and strike motion.

Fault Structures and Morphology

Each fault type exhibits distinct structures. The fault plane is the surface along which the fault slip occurs, while the fault zone encompasses the broader area affected by the fault. Key structures include:

-

Fault Scarp: A steep slope or cliff formed by vertical motion along a fault.

-

Hanging Wall and Footwall: In a normal fault, the hanging wall moves down, while the footwall remains stable. In contrast, reverse faults have the hanging wall moving upward.

-

Fractures are often associated with faults. They are cracks in the rock that may contribute to faulting, especially in active fault regions.

Geological Impacts of Faulting

Faulting significantly alters geological landscapes and can trigger various geological formations. Some impacts include:

-

Rift Valleys: Formed by the downward movement of blocks in normal faulting.

-

Horsts and Grabens: These are raised blocks (horsts) and lowered blocks (grabens) formed by faulting.

-

Compression and Tension: These forces act on rocks, influencing the type of fault that develops. Compression leads to reverse and thrust faults, while tension results in normal faults.

The study of these faults is vital for understanding seismic risks and geological processes.